This is one of a long-term series of posts about Ariadne’s Tribe inclusive Minoan spirituality. Some of these posts, including this one, are revised and updated versions of older articles that I wrote over the course of a decade on the now-defunct Minoan Path blog at Witches & Pagans. All my new Minoan spirituality blog posts can be found here.

The labrys is one of the most iconic symbols of Minoan civilization. A lot of people use the term “double axe” to refer to these artifacts, conflating them with practical tools or even weapons. But they’re not the same thing.

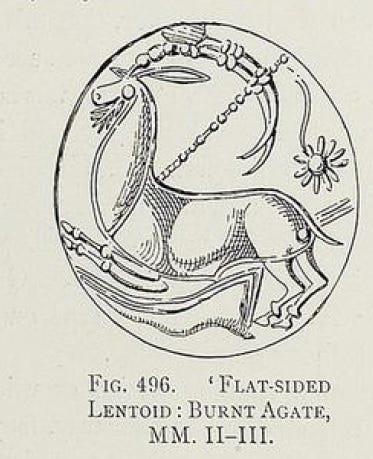

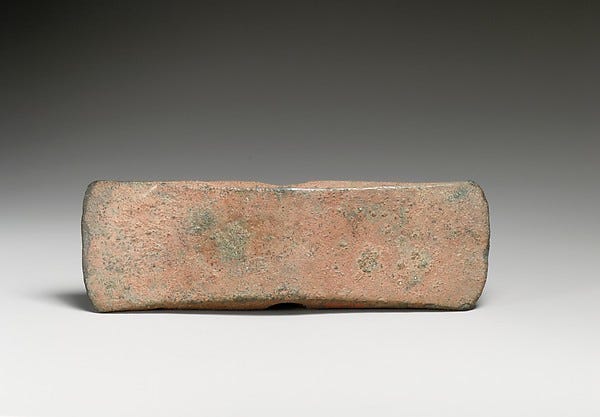

If you look at the many metal labryses found at Minoan sites, you’ll see that they’re all pretty flimsy, made from bronze, silver, or gold sheet metal. The thickest ones would still bend if you tried to use them to chop anything. These bronze ones below are far too thin to be used as actual axes; you can see how the corners have been broken off.

The Minoans did have actual double-bladed axes. Analysis of the wear patterns on their surfaces shows that they were used for chopping wood. But they don’t look like the ceremonial labryses. In fact, they look like modern axes.

The idea of the labrys being used as a weapon dates to Roman times, many centuries after the end of Minoan civilization. And there is zero evidence in Minoan art of anything that looks like an axe or a labrys being used to perform sacrifices.

The only images of animal sacrifice show spears or daggers being used to dispatch the animals; there are no identifiable images of human sacrifice in Minoan art.

When we’re looking at axe-shaped artifacts, we need to make sure to differentiate between the heavy-duty wood-chopping tool and the lightweight religious symbol. The labrys is not really a double axe.

If it’s not an axe, then what is it?

It surely had many layers of meaning for the ancient Minoans. In Ariadne’s Tribe, we consider it to have two primary interpretations (and many further possibilities, but for today we’ll stick to the two main ones).

First of all, it’s a representation of wings. Specifically, it’s a butterfly.

Carol Christ came very close to this idea in a blog post she wrote back in 2013. She understood the idea of wings, but she assumed wings meant ‘bird’ since birds are a prominent symbol of the divine in Minoan art. She didn’t connect the labrys with the many butterflies in Minoan art, though.

If you look carefully at the overall shape of the labrys, you’ll see that it doesn’t mimic a bird’s wings at all, but it does a remarkable job of looking like a butterfly, right down to the ‘body’ section in the middle. On some Minoan ceramics, the comparison is direct, with short-handled labrys butterflies fluttering over fields of flowers next to longer-handled vegetative labryses growing among the flowers and sprouting little tendrils around their blades (we associate vegetative labryses with Ariadne in the mythic cycle of the Minoan Mysteries).

Why would the Minoans want to use butterfly symbols as the focal point for their worship? Because of the wonderful, layered, magical symbolism of the butterfly. Let’s look at those layers.

First there’s the basic transformation that every school child knows about, from egg to caterpillar through the cocoon stage to the butterfly. Nature is magic!

Butterflies have long signified the human soul in cultures around the world. As I made my way around the internet to research this blog post, I was amazed to discover that these beautiful insects are still linked with the beloved dead today, and in a truly unique way: they often appear as a sign of after-death communication from loved ones. The ancestors are always with us.

There’s one more layer of symbolism to the labrys that brings the process full circle.

In addition to looking like a butterfly, the labrys looks like a vulva – the external female genitalia. The ‘wings’ are the labia, and the ‘butterfly body’ in the center is the clitoris. [Please use the proper term, vulva, for the external genitalia. The word vagina refers to an internal organ.]

Why is this symbolism important? Because it’s through the vulva that we’re born into this world. The butterfly is the soul, and the vulva is the gateway through which it enters the world, to return to incarnation among the beloved.

You can look for further symbolism, if you like, in the pole that many labryses were mounted on. A pole that’s inserted into a vulva – what do you think that might be?

While the Victorian-era archaeologists who dug up the ancient ruins on Crete might have been titillated by this idea, we should recognize that to the Minoans, as with other matrilineal societies, sexuality in all its forms was most likely a sacred and joyful subject and would have been regarded with respect and joy, not embarrassment.

So the next time you see a labrys, instead of picturing some ancient warrior wielding it, try imagining it coming to life and taking flight, its butterfly wings flashing gold in the sunlight, reminding you that there’s more to life than first meets the eye.

I’m not planning to paywall my Substack, but if my work has meaning and value for you, please consider dropping a little something in my tip jar at Ko-Fi. Thank you!

You can find my books here and my art here and here. I do apologize, but due to unpleasant activity from trolls, I’ve had to limit comments to subscribers only. I hope you understand.

About Laura Perry

I’m the founder and Temple Mom of Ariadne’s Tribe, a worldwide inclusive Minoan spiritual tradition. I’m also an author, artist, and creator who works magic with words, paint, ink, music, textiles, and herbs. My spiritual practice includes spirit work and herbalism through the lens of lifelong animism. I write Pagan / polytheist / magical non-fiction and fiction. My two latest books, Pantheon: The Minoans and Tales from the Labyrinth, are now available. I do more than just write and make art: I’m also an avid herb and vegetable gardener and living history demonstrator (heritage interpreter).

I love this! I suspected the butterfly but not the vulva symbolism. You made my day!

Brilliant! Thank you